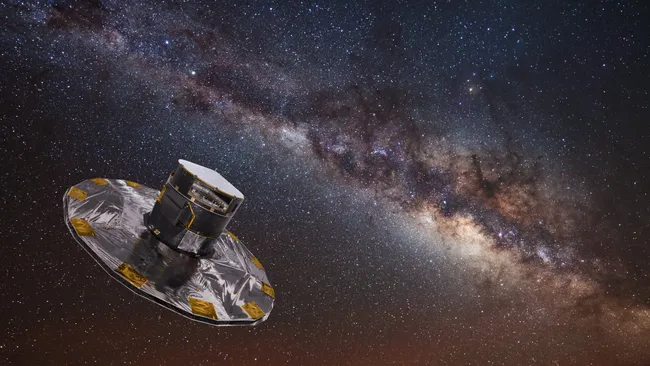

On March 27, scientists bid farewell to the Gaia space telescope, marking the end of its transformative 11-year mission mapping the Milky Way and its surrounding cosmic neighborhood. While it never gained the public spotlight like Hubble or James Webb, Gaia has profoundly reshaped our understanding of the galaxy we inhabit. Since launching in 2013, the European Space Agency’s spacecraft has systematically charted the cosmos, compiling an immense catalog of nearly 2 billion stars, over 4 million candidate galaxies, and approximately 150,000 asteroids—some possibly with their own moons.

Its contributions have underpinned more than 13,000 scientific papers to date, a number that’s expected to grow significantly in the years ahead. “Gaia’s extensive data releases are a unique treasure trove for astrophysical research, and influence almost all disciplines in astronomy,” said Johannes Sahlmann, project scientist for the mission. Gaia operated nearly twice as long as originally planned before running out of fuel, at which point ESA powered it down and retired the spacecraft.

>>>50906550E Replacement Battery for Vsmart Star 5

Positioned at Lagrange Point 2, about 1.6 million kilometers from Earth, Gaia’s primary objective was to create the most accurate 3D map of the Milky Way ever assembled. To accomplish this, it employed two telescopes and three science instruments capable of recording precise measurements of stellar position, velocity, color, and composition. This unprecedented map revealed the galaxy’s spiral structure in greater detail, offered new estimates of the dark matter halo enveloping it, and provided evidence that the Milky Way’s disk is warped and wobbling—likely due to an ongoing collision with the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy.

Gaia also altered the timeline of galactic evolution, showing that stars began forming in the Milky Way’s disk less than a billion years after the Big Bang—far earlier than the previously assumed 3-billion-year mark. It uncovered vast, previously hidden stellar structures like the Radcliffe Wave, a 9,000-light-year-long string of star-forming regions, and serendipitously detected thousands of starquakes—subtle ripples on the surfaces of stars that help reveal their internal structure. High-velocity stars, black holes surprisingly close to Earth, and streams of stars that trace the remnants of long-vanished galaxies are all part of Gaia’s legacy. Its measurements have even fed into the ongoing debate around the expansion rate of the universe, offering new data that complicate the current cosmological model.

ESA officially decommissioned Gaia on March 27, using the spacecraft’s remaining propellant to send it into a graveyard orbit, safely out of the way of future missions at L2. Engineers then deliberately corrupted its onboard software to ensure it would never reactivate, even if its solar panels caught sunlight. “We had to design a decommissioning strategy that involved systematically picking apart and disabling the layers of redundancy that have safeguarded Gaia for so long,” said spacecraft operator Tiago Nogueira. To commemorate the mission, the names of all 1,500 contributors were uploaded into the onboard memory, alongside personal farewell messages and poems.

>>>ER6C Replacement Battery for Maxell ER6C

Though Gaia has gone silent, its scientific legacy is far from over. Only about a third of the data it collected has been processed to date—by the end of the mission, Gaia had gathered more than 1 petabyte of raw data. The next data release is scheduled for 2026, with the final release expected by 2030, covering the full decade of observations. As Anthony Brown of Leiden University put it, “Gaia has been the discovery machine of the decade—a trend that is set to continue.”